King Lear: A Verse Translation, 2e

King Lear: A Verse Translation, 2eWilliam Shakespeare

Kent Richmond (translator)

ISBN-13 9780983637943

Full Measure Press

King Lear: A Verse Translation, 2e

William Shakespeare

Kent Richmond (translator)

ISBN: 978-0-9836379-4-3

Full Measure Press

Two families torn

by jealousy,

ingratitude, and rage

drive a kingdom

to civil war

and madness.

This revised 2nd edition of King Lear: A Verse Translation makes the language of Shakespeare's play more modern while preserving the rhythm, complexity, and poetic qualities of the original. The aim is to capture the sound and sense of Shakespeare's tragedy without the need for glosses or notes--to use contemporary language without simplifying or modernizing the play in any other way.

Shakespeare’s play is about 75% verse and song and 25% prose. To make the play seem as much like Shakespeare’s original as possible, Kent Richmond maintains that exact ratio. His blank verse is accurate and representative of what Shakespeare used. He also uses a range of vocabulary and sentence complexity that matches the original closely. Shakespeare no doubt wanted his play to be difficult and challenging and Richmond’s translation respects that desire. [read an excerpt]

Number of Unique Words

Shakespeare's original: 4,093

Richmond's translation: 4,283

Is King Lear Shakespeare’s greatest play? Those who love Hamlet will certainly have something to say on the matter, but it is hard not to be awed by Lear’s intense poetic expression as Shakespeare weaves together two stories of shocking brutality.

Experience the violent downfall of Shakespeare's most dysfunctional family with the comprehension and delight of audiences 400 years ago—the way Shakespeare intended.

Excerpt from King Lear: A Verse Translation

from Act 1, Scene 2

Scene Two. A Hall in Gloucester’s Castle

[Enter EDMUND with a letter]

EDMUND

Read another excerpt

You, nature, are my goddess. To your law

My services are bound. For why should I

Endure the plague of custom, and thus let

The legal niceties of states deprive me,

Because I trail a brother by some twelve

Or fourteen moons. Why bastard? Why debased?

When my physique is just as well composed,

My mind as noble, and my shape the same

As lawful wives bring forth? Why brand us then

As base? With baseness? Bastardly? Debased?

Don’t we from stealthy acts of natural lust

Receive more character and fiery vigor

Than comes from all the dull, stale, tired beds

That go to make whole tribes of fools conceived

Between the time we sleep and wake? Well then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land.

Our father loves the bastard son as much

As the legitimate. Fine word—legitimate!

Well, my legitimate, if this letter works,

And if my scheme goes well, Edmund the base

Tops the legitimate. I grow. I prosper.

Now, gods, stand up for bastards!

© 2004 by Kent Richmond

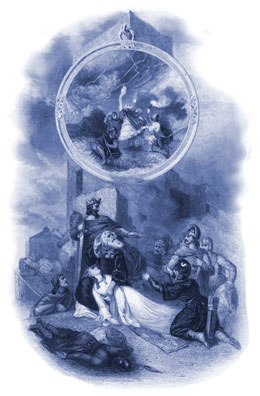

Read an excerpt from

King Lear and Cordelia

Praise

"Too often, unless we read a Shakespeare play beforehand, we process the language as if it were coming from a poorly tuned-in radio station. Shakespeare didn’t write his plays to be experienced impressionistically as ‘poetry;’ he assumed his language was readily comprehensible. At what point does a stage of a language become so different from the modern one as to make translation necessary? Mr. Richmond is brave enough to assert that, for Shakespeare, that time has come. The French have Moliere, the Russians have Chekhov—and now, we can truly say that we have our Shakespeare.”

—John McWhorter, Manhattan Institute